Insensitive comments and microaggressions are an unfortunate aspect of America’s diverse society

October 25, 2020

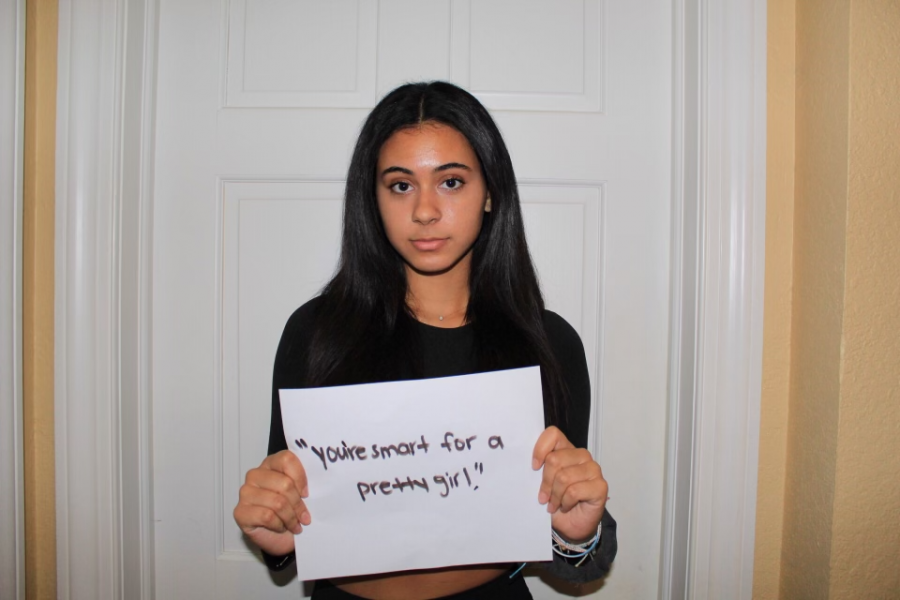

“You’re the whitest Black person I know.” “You don’t like me though, right?” “But why can’t you show your hair?” These are some of many sayings that are normalized in society when in reality they are ignorant and hurtful; they are considered microaggressions. The Oxford definition of a microaggression is “a statement, action or incident regarded as an instance of indirect, subtle or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group such as a racial or ethnic minority.”

The term microaggression was coined in 1970 by Chester M. Pierce, a Black psychiatrist and Harvard Medical School professor, after he endured years of segregation and later subtle racism. Over the following decades, psychologists have continued to expand on Pierce’s ideas and began exploring the reasons humans engage in these aggressions.

Microaggressions result from both our natural-born implicit bias and generations of perpetuating inaccurate stereotypes. Implicit bias refers to the skewed perception of certain things, people or events due to our upbringing. As we grow up, everything that we see, hear or experience molds our view of the world and all it has to offer.

Someone who lived a very sheltered life in an area with a very homogeneous population would have a very different perspective on people of other races, ethnicities and sexual orientation than that of a person who lived in a diverse neighborhood with all kinds of people. This bias, along with the stereotypes society instills into our minds, are often the main contributors to misunderstanding those who are different from us.

“For me, I feel that being a black teen with many white peers, I am always questioned about my heritage. I have heard comments such as ‘you act white’ or ‘you don’t sound Black,’ questioning my culture that people who don’t know me will [expect,]” senior Jevaughn Morris said. “I feel that it is so normalized because it allows minorities to fit in their social groups by laughing at these types of jokes that are back-handed compliments. I wouldn’t overreact over a microaggression with friends, because of the relationship I have with them, [although] I would see it as disrespectful for a stranger to say a back-handed compliment to me.”

There are three subcategories of microaggressions: microassault, microinsult and microinvalidation.

Microassaults are verbal or nonverbal attacks inflicted on another person for the sole reason of being discriminatory. These assaults are the most aggressive form of microaggressions and most commonly consist of slurs.

Microinsults are subtle remarks or actions that are condescending to a racial group, sexuality, ethnicity or gender. These are not always intentional and can stem from one’s implicit bias.

Microinvalidation describes the negligence of a minority’s thoughts, feelings and reality. Statements such as, “I know we are both ‘American’ but where are you really from?” or assuming that a Muslim woman must be oppressed because she wears a hijab are deemed microinvalidations.

“Once I was kicked out of my friend’s house because her dad didn’t like who I was and said, ‘I know what you are.’ I was respectful, however, and just apologized because I didn’t know what else to do. This was before I even came out and only a few friends knew about my sexuality,” senior Brandon Dietrich said. “I just don’t understand why people need to be involved in other people’s races, sexuality or religions if it doesn’t concern them. People should educate themselves and understand other people’s cultures and their background and they shouldn’t talk for other people if they aren’t a part of that subculture.”

While microassaults occur when someone is unapologetically being intolerant, microinvalidations tend to be more common as an underlying form of ignorance.

“I don’t have a particular story to tell, but I have faced situations [of discrimination] in the past that were often turned into a joke, or [were] made out to be no big deal,” junior Molly Winkleman said. “Growing up, I would get comments about my small eyes, asked if I eat dog and hear people call out ‘ching chong’ or something along those lines. At first, I would feel hurt and offended, but people would make my feelings invalid, so after a while, I had to learn to ignore them.”

Social settings are not the only places where microaggressions can ensue. Our implicit bias follows us everywhere, including professional and educational environments. In both the workplace and classroom, there are various laws and regulations in place to protect both employees and students from acts of discrimination, yet that does not mean that microaggressions still do not occur.

“I have been put in the uncomfortable situation of having all heads turn towards me whenever there was the mention of terrorism or 9/11” senior Alishba Hashmi said. “No one would ever say anything, but [they] would assume I would know more on the topic because I am Muslim.”

Particularly in school, the preconceived notions of teachers, administrators and other students have resulted in insensitive comments or actions.

“I remember being in 5th grade when I had put on henna, which is a temporary tattoo significant to my culture, and being made fun of by the boys in my class. I ended up covering my hands with my sleeves because I was embarrassed,” senior Emaan Ali said. “I believe microaggressions are so normalized in such a diverse country because there are still stereotypes that are inflicted upon different racial groups that lead people to make assumptions about someone’s culture or make fun of it without considering its significance.”

In 2017, New York University professor and sociologist Hua-Yu Sebastian Cherng conducted a study measuring implicit bias in schools. Cherng observed classrooms and discovered that the math teachers at that school “perceive their classes to be too difficult for Latino and Black students, and [the] English teachers perceive their classes to be too difficult for all non-white students.” The study also reveals the direct correlation between teachers’ faith in their students and the students’ success.

Assumptions based on race, sexuality or ethnicity do not only occur inside the classroom. The implicit bias of staff members outside of the hallways such as administrators and security guards can also take a toll on students.

According to GLSEN, an organization formerly known as the Gay and Lesbian Independent Teacher Network, 28.2% of LGBTQ+ students have been disciplined for brief public displays of affection that their straight counterparts often engage in. Situations similar to this have caused students to experience feelings of abnormality and inferiority, which can directly impact their mental health.

Constant exposure to microaggressions is reported to have detrimental effects on the well-being and self-esteem of minority students. These statements play a huge role in the operation of one’s psychological health and reasoning, impacting their behavior. Feelings of inferiority and the pressures of breaking stereotypes are common challenges that victims of microaggressions experience.

“Being a person of color in a predominantly white school has always made me feel different,” junior Sophia Millet said. “I always felt like an outsider compared to my white friends, and I used to do everything I could to deny myself of my culture. I stopped speaking the language [and] started acting and dressing like my friends did because I felt that the way I am was not enough. Ever since I was a kid, people always made racist assumptions about me and it always made me so upset. A lot of people would use microaggressions and think that what they were saying was okay and not offensive, when in reality it’s not okay to say to someone.”

Since America is made up of an extremely diverse population, our differences tend to be at the forefront of our lives and often can lead to insensitive inquiries or comments.

“I think microaggressions are so prominent even in such a culturally diverse society because we still live in a world where certain attributes have a stigma around it,” Ali said. “People tend to depend on the stereotype that society has made of unfamiliar groups of people to make themselves feel a bit more familiar with the situation; even though that may not always be the case.”

On the national level, campaigns such as “I too am Harvard” and films such as “Dear White People” have been developed in order to raise awareness regarding microaggressions and educate people about what might be considered a microaggression and how it impacts others.

“I feel like microaggressions have become so normalized because they aren’t seen as direct attacks to a person, more as a ‘funny’ offensive joke,” senior Fabian Cazorla said.

According to a survey of 412 MSD students, 74% of students who engaged in a microaggressions were not aware of the impact or consequences of their action or statement.

“I think many times people don’t mean to be stereotypical, but the way a question is posed can alter the way it is interpreted,” Winkleman said. “It is important to think about what you are saying before you say it because it is so easy for a sentence to be misconstrued and taken the wrong way. Microaggressions have affected my life the most because well-intentioned people often make ignorant comments.”

This story was originally published in the October 2020 Eagle Eye print edition.