Lending a Hand

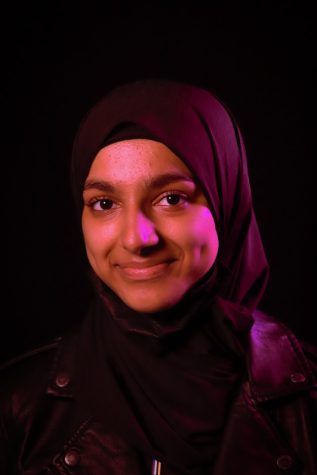

MSD senior Kayla Behmardi is the co-president and co-founder of the Red Cross Club. The Red Cross Club aims to encourage students to support charitable acts through various service missions to build safer communities through the non-profit humanitarian organization American Red Cross.

Senior Kayla Behmardi’s commitment to the MSD Red Cross Club has inspired her future profession

After rigorous social media campaigning and a virtual presentation, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School’s Red Cross club proudly raised 680 dollars for “Vaccinate a Village,” a fundraiser aimed to raise funds for the Measles and Rubella institute.

Senior Kayla Bedmardi is both the co-president and co-founder of the Red Cross Club, alongside senior Haya Shaikh. The Red Cross Club aims to encourage students to support charitable acts through various service missions to build safer communities through the non-profit humanitarian organization American Red Cross.

“The MSD Red Cross Club is a club dedicated to serving our community and communities around the world by engaging in projects about disaster preparedness, emergency first aid, humanitarian aid and international humanitarian law,” Behmardi said.

Duties as co-president include coordinating club activities, planning meetings and attending conferences with other regional Red Cross volunteers. First starting the club in their sophomore year, the Red Cross Club has grown throughout the past two years and now has 119 members. They meet on the second Monday of every month in social science teacher Sofia Capezza’s classroom.

Alongside her commitment to the Red Cross Club, Behmardi also juggles a job at MOD Pizza with taking challenging honors courses at school. She works as a line cook for approximately 15 to 20 hours per week.

“Managing a job and volunteering [for the Red Cross club] can be difficult sometimes, but luckily my co-president and the other officers are really good at working together, and if one person is overwhelmed, the other officers can step in and help out,” Behmardi said.

Behmardi receives a lot of her dedicated work ethic from her parents who immigrated from Iran. As a child of immigrant parents, Behmardi has demonstrated true determination.

“My parents didn’t have anything when they came here, so they had to work extra hard to create a future for our family,” Behmardi said. “I think I get my work ethic from them, and I just want to make them proud.”

The Iranian culture involves customs and practices that are often overlooked. For instance, many people do not realize that it is considered offensive to sit with your back to someone. Iranians riding in the front passenger seat of a car will even apologize to the passengers behind them for having their back facing them.

Additionally, rather than snapping, Persians “beshkan,” which is a different version of applauding. To beshkan, you connect both hands to make a loud snap with your index fingers, which is frequently seen during parties or other ceremonies like high school graduations.

Some of these Iranian practices and customs transfer to Behmardi’s own household, such as drinking tea. In Iran, Persian tea is the frequent drink of choice and is served with all three meals of the day.

Living in America her entire life, Behmardi continuously faces challenges as an Iranian-American. She often feels like she is stuck in the middle, as she is not viewed by others as either fully American nor Iranian.

Applying for colleges, Behmardi feels conflicted on what box to check off for the race column. Behmardi considers herself Iranian-American, but since that is not an option on official forms, she is forced to check the “white” box.

“I don’t like that being Middle Eastern classifies you as white because I don’t think it properly reflects the identity and experiences of Middle Eastern people,” Behmardi said. “I feel like every time I have to check the ‘white,’ box I’m lying.”

The race section on college applications, which is required, typically consists of American Indian or Alaska Native (indigenous peoples of Alaska), Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander and White. With no Middle Eastern option, applicants like Behmardi, are forced to check off the ‘white’ box. College applications, such as Common App, do not even include an “other” option, leaving people of Middle Eastern descent often feeling underrepresented.

People may mistake those from the Middle East as white due to their pale skin tones. However, skin color does not always coincide with race.

“I think the challenges of being Middle Eastern have a lot to do with xenophobia and islamophobia,” Behmardi said. “There are always going to be people out there who treat you like a foreigner or a villain because of where you’re from.”

Xenophobia is fear towards strangers, or foreigners, which frequently leads to hate and violence. Many white supremacist groups, like the Ku Klux Klan, are examples of xenophobic behavior. Islamaphobia is the distinct prejudice towards Islam and Muslim cultures.

Though Behmardi faces challenges being Iranian-American, she has learned to push through them and be herself. She aspires to strengthen her current dedication by pursuing a career in medicine after attending an accredited university, specifically the University of Florida, with a major in health science.

“I think biology is fascinating, and there are a lot of ways to make a difference in medicine,” Behmardi said.

With family members currently in the biology field and her current role in the Red Cross club, Behmardi feels inspired to join them. Through the pursuit of her passions, she can prove that being the child of immigrants does not take away her ability to succeed, if anything, it strengthens it. She hopes to make an impact by saving lives in the future with her medical degree.