MSD students fear the effects of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill

Tribune News Service

Moses May, 14, leads a student protest at Gaither High in Tampa, Florida, against what critics call the “Don’t Say Gay” bills, on Monday, Feb. 14, 2022. Courtesy of Ivy Ceballo/Tampa Bay Times/TNS.

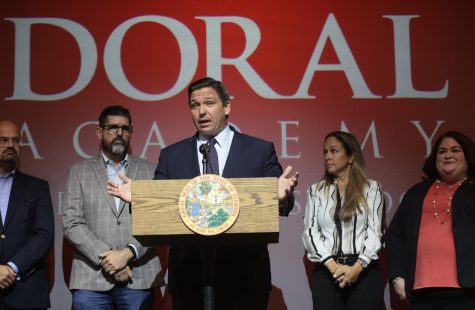

Known widely as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, House Bill 1557 states that instruction from school staff or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity is not allowed in kindergarten through third grade or in a way that is seen as inappropriate by the state’s standards in other grade levels. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the bill, also known as the “Florida’s Parental Rights in Education” bill, into law on Jan. 20.Supporters of the bill reasoned that parents should have the right to control what their young children hear at school. If a parent or guardian believes the school broke the law, they have legal standing to sue the district and possibly get teachers, staff and administration fired.

While the bill does not say the word “gay,” it does use the phrase “sexual orientation” and “gender identity.” It also uses the term “age-appropriate” when referring to these topics; many people have different opinions on what age is appropriate to discuss sexual orientation and gender and what age is not. These phrases have caused controversy throughout the state because of the imprecise language used.

The “Don’t Say Gay” bill is just one bill out of many in various legislatures around the country that are anti-LGBTQ+. States such as Georgia, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Kansas and Alabama have already written and are trying to sign off on similar bills to the “Florida’s Parental Rights in Education” bill. All of these bills give some sort of variation that schools cannot talk about sexuality, gender identity or any related subjects.

This bill has sparked protests from Florida students around the state, some of whom have organized walkouts at their schools.

“I think [this bill] is sad because it’s just going to suppress their feelings and make it harder to work through their internalized homophobia later on,” freshman Rashi Garg said.

Internalized homophobia happens when queer people assume everyone is or should be heterosexual. It is a form of oppression that ignores the needs and experiences of queer people. With these laws, students believe internalized homophobia will become more prominent.

“I feel bad that they can’t feel comfortable talking about their own sexuality because if they can’t feel comfortable in one place, that uncomfortable feeling will spread to other places,” sophomore Justus Garfield said.

Comfortable is defined as a mental or physical state of being content or at ease. The HRC Foundation and the University of Connecticut conducted a survey in 2018 to show the amount of LGBTQ+ students that felt unsafe in school due to stress, anxiety and rejection. The survey received over 12,000 respondents from ages 13 to 17 from all 50 states. The percentage of students that felt that their families would not be supportive of the contents of this bill is 76%, and the numbers may rise.

Moreover, worries that internalized homophobia and uneasiness about sexuality will increase and cause trouble within schools. While it is uncertain how the law will turn out, the LGBTQ+ community will carry on speaking against the bill regardless of whether their competing party defends the claim that the law advocates for parental rights.