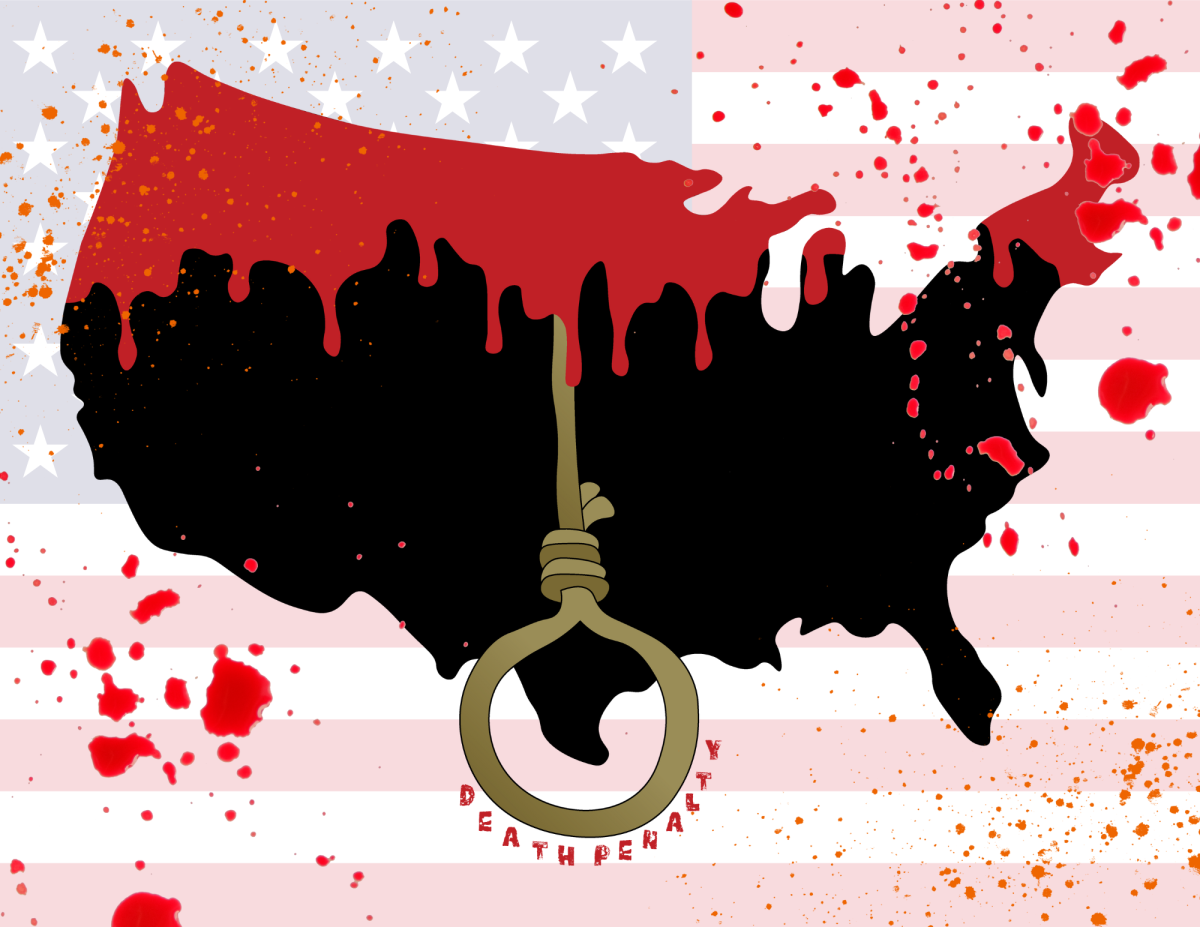

To be given the death penalty is the highest possible sentence one can receive for a crime in the United States, one meant only for people who have committed the most heinous and egregious of crimes. So, imagine the nation’s shock and outrage when on Tuesday, Sept. 24, an innocent Missourian man was executed for a crime he did not commit.

This was the tragic reality of Marcellus Williams, a 55-year-old poet and devout Muslim who was accused of murdering 42-year-old Felicia Gayle. Gayle was a former police reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch who died after being stabbed 43 times in a home invasion in her St. Louis residence on Aug. 11, 1998.

“The state of Missouri and our nation’s legal system failed Marcellus Williams,” Missouri Representative Cori Bush said. “As long as we uphold the death penalty, we continue to perpetuate this depravity–where an innocent person can be killed in the name of justice.”

Since being sworn in on June 1, 2018, Missouri Gov. Mike Parsons has put 12 inmates to death, with Williams being the most recent. The death penalty in America is already a system of punishment with unjust roots. Black defendants are four times more likely to be sentenced to death than white defendants for similar crimes.

Williams is a prime example of the injustices within the American judicial system and the impact it can have on the lives of citizens around the country.

In 2001, Williams was convicted of murder and put on death row. The majority of the prosecution’s case was based on the accounts of two unreliable and incentivized witnesses: Williams’ former girlfriend Laura Asaro and jailhouse informant Henry Cole.

Law enforcement was first notified about the case after Gayle’s husband Daniel Picus came home from his office job to find Gayle’s lifeless body on the stairs leading to their bedroom. Picus immediately called the police, who arrived a short time later.

At the crime scene, law enforcement found a wide array of evidence including hair samples found on the victim and floor, shoe prints, a knife sheath, bloody fingerprints on the wall around the body and the murder weapon.

Along with DNA samples, law enforcement found that items were taken from the home in the burglary: a ruler, a calculator and Picus’ laptop. The missing items were used as key evidence of Williams’ guilt, as Asaro’s testimony stated that she had discovered them in Williams’ car. When Asaro questioned Williams about the items, she claimed that he told her about the murder and threatened to harm her and her family if she told anyone.

Her testimony would seem to be corroborated when over a year after the start of the investigation, while Williams was in jail for a different offense, law enforcement searched the vehicle with permission from Williams’ grandfather and found the ruler and calculator.

Around that time, police would recover Picus’ laptop from a man named Glenn Roberts, claiming that he received the laptop from Williams, who admitted to pawning it off.

Also, over the course of this year, Williams met and befriended Cole, a prisoner being held in the same area as Williams. Cole claimed that while they were doing labor, Williams admitted to him that he committed the crime and told him the details. Cole wrote these confessions on a spare sock with a pen and turned his findings in to law enforcement a short time later.

Due to these two witness testimonies, Williams was indicted and tried for Gayle’s murder, being found guilty on all counts in his 2001 trial and sentenced to death with a vote of 11-1 from his jury.

While on paper this would be seen as strong evidence pointing towards Williams’ guilt, when looking at the full picture, the validity of the evidence presented and the discoveries made are extremely questionable. This starts with what was found at the scene of the crime.

The physical evidence found in Gayle’s home was not considered in Williams’ original trial. This became evident when over a decade later, in 2015, forensic analysis and DNA testing concluded that none of the evidence found at the scene of the crime was a match to Williams. Later, in 2017, even more tested DNA samples from the scene were found not to be at all connected to Williams.

Prior to the car search and the discovery of the missing items, the investigation had slowed down exponentially and gone cold due to the lack of leads and evidence at the time. Becoming increasingly frustrated with the process of the investigation, Picus offered a $10,000 reward to anybody that could find a lead in the case.

Incentivized witnesses are people in a case whose testimonies cannot be considered fully reliable due to police interference or imposed bias. People are often persuaded to give a confession or a testimony when offered rewards such as money, reduced prison time and/or pardons from prison. This is how Cole and Asaro come into play.

At the time, Cole was a 12-time career criminal with convictions spanning over 30 years, including robbery, burglary and multiple weapons offenses. In early May, while Cole and Williams were watching television, a news story came on reporting about Gayle’s death and the $10,000 reward.

Shortly after, Cole started reporting to the police about confessions made by Williams. In his testimony, however, none of the details he shared included information not reported by the media or known by law enforcement already. Cole stated multiple times during his testimony that he was only giving details about Williams’ involvement for the reward money. After his testimony, Cole repeatedly called police and law enforcement asking about the reward.

In total, Cole received $5,000 and a removal of his prison sentence for a 1996 bank robbery. Cole also tried to call Asaro multiple times after being released from prison, but she did not return these calls. Still, like in Cole’s case, Asaro’s testimony can also be called into question. Asaro claimed that Williams had visible scratches and cuts on his body, but when examining the physical evidence, none of Williams’ DNA was found under Gayle’s fingernails.

Additionally, in his 2001 trial, Williams stated that he received the items missing from Gayle’s home from his girlfriend a while after the crime. While on the surface this may seem like a lousy excuse, looking into Williams’ and Asaro’s actions before and after the crime paints a clearer picture. For example, the laptop that was pawned by Williams corroborated his claims.

Glenn Roberts, the man who received the laptop from Williams, gave a testimony claiming that Williams had explained to him while selling it that he received the item from Asaro. In August 1998, the month the murder occurred, Williams’ brother stated that Asaro even called him to ask if he would like to buy a laptop from her for $100. That same month, Williams’ 10-year-old cousin witnessed Asaro get off of a bus carrying the computer. Plus, Asaro had access to Williams’ car even after he was in jail.

Thus, the claim that Williams is guilty is loosely based at best. The Missouri justice system failed to paint a full picture of the case to the jury, resulting in the lynching of a man who had strong evidence proving his innocence.

From his conviction to the time of his death, Williams maintained his claims of innocence, while using his final years in prison to turn to education and Islam to follow a more righteous path of life. Before his execution Williams’ final words were a single phrase: “All praise be to Allah in every situation.”

The case of Williams is a reminder of the constant failure of the U.S. legal system to uphold the truth and sentence defendants fairly with an unbiased standpoint, especially towards black and brown victims.

Statistics by the U.S. Sentencing Commision state that on average, black male offenders receive 20% longer sentences than white male offenders. Black men are also significantly less likely to receive pardons or parole agreements than white offenders for the same crime, meaning that cases like the treatment of Williams by the court system are devastating but not surprising.

Today, Williams’ fight for freedom serves as a symbol of hope and highlights systemic injustice.