“In times of social turmoil, our impulse is often to pull back on free expression,” Mark Zuckerberg said to Georgetown University students in 2019. “We want the progress that comes from free expression, but not the tension. We saw this when Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his famous letter from Birmingham Jail… We saw this in the efforts to shut down campus protests against the Vietnam War. We saw this way back when America was deeply polarized about its role in World War I… In the end, all of these decisions were wrong. Pulling back on free expression wasn’t the answer and, in fact, it often ended up hurting the minority views we seek to protect.”

Free expression is a cornerstone of American democracy. As society becomes increasingly digitized, social media platforms–like Zuckerberg’s platforms of Instagram and Facebook–have had an increasingly prominent role to play in such expression. This change has brought about many questions, specifically regarding the blurred line between what is content moderation and what is censorship.

The First Amendment spells out that “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” The amendment makes governmental censorship of free speech unconstitutional, protecting the right of Americans to speak on issues that concern them, even when their opinions are critical of the government.

However, while the First Amendment protects speech from government censorship, it does not protect it from censorship by private organizations, businesses and citizens. These distinctions are pertinent to conversations regarding social media platforms, which are private, international companies often regarded as forums for free speech.

“I believe that social media allows for free speech,” freshman Anika Polapally said. “Social media literally lets users express their opinions with forums, making their own videos and commenting. Millions of people who view your video or comment can see what you have to say.”

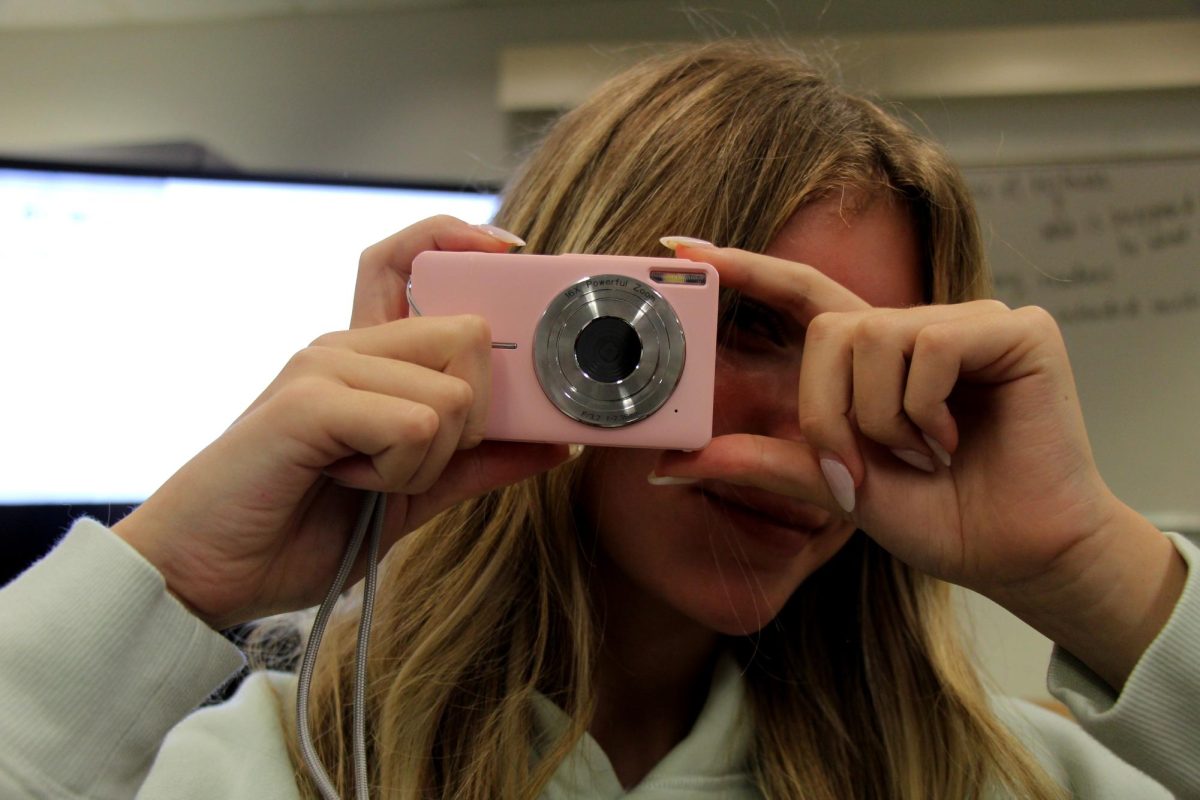

In particular, many teens attempt to use social media platforms to exercise their First Amendment rights. After all, most teens use these sites regularly. According to Pew Research Center, in 2023 the majority of 13-17-year-olds reported using TikTok, Instagram, YouTube and Snapchat.

These findings ring true among Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School students as well. In a survey of 333 MSD students conducted by Eagle Eye News, 73% reported using TikTok, 80% reported using Instagram, 4% reported using YouTube and 68% reported using Snapchat.

“I use social media pretty much every day,” sophomore Maliah Smith said. “I spend a lot of time on it for communication and entertainment purposes. I text my boyfriend and best friend on Snapchat, so I am constantly on that, and I use TikTok to stay updated on my friends’ lives and just to watch when I’m bored. Many influencers and celebrities are on TikTok that I have started liking and it is fun to follow along on their journey.”

Given teenagers’ social media presence, any censorship that occurs on social media platforms disproportionately affects their demographic.

Algorithmic Bias

Since social media platforms are private companies and cannot be held liable for violating the First Amendment, they are capable of censoring users. As allowed by Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, online platforms can moderate their content by their own standards, which includes practices such as removing posts that violate self-imposed community guidelines.

Content moderation is the practice of monitoring, reviewing and regulating content to ensure that it abides by community guidelines. It attempts to hinder the spread of content that is hateful, discriminatory, violent, misinformed or otherwise harmful to viewers. Moderation is a form of censorship, but it is one that social media companies are entrusted to do in good faith and for the protection of their users.

Nowadays, algorithms are typically used for content moderation, which is the case for YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok and many other major social media platforms. Unfortunately, algorithms, just like people, have the capacity to be flawed.

For one, the implicit biases that persist throughout society may also have the ability to infiltrate artificial intelligence systems, namely via their developers or the training data used to teach AI how to make decisions. According to Harvard Business Review writers James Manyika, Jake Silberg and Brittany Presten in the article “What Do We Do About the Biases in AI?” algorithms may be biased if their training data contained biased human decisions, reflected historical or social inequalities or over or underrepresented groups of people.

“Social media algorithms can be biased,” freshman Zane Maraj said. “These biases often stem from the way algorithms are programmed, which is influenced by the data they are trained on and objectives set by the platform. For instance, algorithms prioritize engagement, meaning they show content that is more likely to evoke reactions, such as controversial or polarizing posts. This can inadvertently amplify certain viewpoints over others.”

Algorithms amplify biases as they moderate content, potentially flagging or removing posts that are not actually harmful, as well as shadow-banning users.

In the words of Geoffrey Fowler in the 2022 Washington Post article “Shadowbanning is real: Here’s how you end up muted by social media,” shadow-bans are “a form of online censorship where you’re still allowed to speak, but hardly anyone gets to hear you.” It is not uncommon for content creators to allege that they are being shadowbanned, despite the fact that social media companies are known for being untransparent about the practice on their platforms.

Shadow-banning and the removal of posts by algorithms often come about as a result of the use of certain hashtags, words and images. For instance, TikTok users discovered in 2021 that the term “Black people” was flagged as inappropriate by the algorithm, while the term “white supremacy” was not.

To avoid these things many creators have taken to self-censoring, mouthing or altering the spelling of certain words. For instance, it is not uncommon to see people replace the word “kill” with “unalive,” or the word “suicide” with “sewer slide” on social media to prevent algorithmic detection.

With that being said, it is also important to note that all of this may not be solely attributable to algorithmic bias. Algorithms are not yet able to fully recognize and interpret social context, which is necessary for them to accurately detect and remove hate speech from social media sites.

“Hate speech and talking about hate speech can look very similar,” University of Colorado, Boulder Assistant Professor Casey Fiesler, who studies technology ethics and online communications, said to MIT Technology Review in the 2021 article “Welcome to TikTok’s endless cycle of censorship and mistakes.”

Oftentimes, the same terms used in hate speech are used when creators discuss their experiences on the receiving end of it. As a result, algorithms may recognize certain words, but fail to adequately interpret the context in which they are being used. Biased or not though, the same people end up being censored.

“Algorithms may be biased against smaller creators or marginalized groups because they tend to favor content from accounts with higher engagement, often reinforcing popular narratives and sidelining less mainstream voices,” Maraj said. “Additionally, biases in moderation practices can disproportionately impact minority communities or politically sensitive topics.”

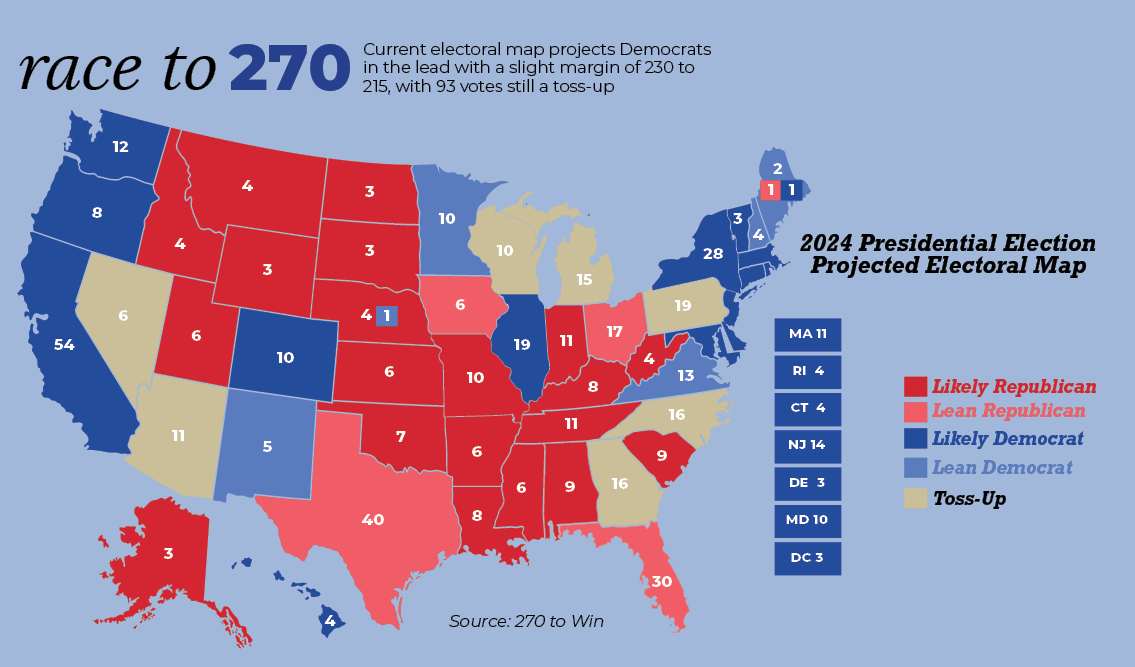

On top of censoring minority creators, it is also the general belief of Americans that social media algorithms censor political opinions. A 2021 Pew Research Center study, found that seven in 10 adults reported believing that algorithms used to detect false information were either definitely or probably censoring political viewpoints.

“I think social media algorithms have a right leaning bias because of the amount of content leaning towards the right, such as conservative commentary/clickbait on YouTube and Elon Musk’s proliferation of alt-right content on Twitter while demeaning left-wing content,” senior Vinh Nguyen said.

Echo Chambers

The primary purpose of a social media platform’s algorithm is to maximize user engagement by recommending viewers agreeable content that keeps them gripped and coming back. The algorithm learns what users want to see by the way they interact with content, and then uses that information to inform what kind of content it will show those users in the future.

Many find that this practice undermines free speech. By only showing people content that confirms their beliefs, algorithms are effectively dividing people with clashing views into two separate echo chambers. Echo chambers are environments in which people only hear opinions, information and ideas that align with their pre-existing views.

“I’ve noticed this [echo chambers] on social media a lot, and I believe it’s a bad thing,” freshman Dan Iusim Siler said. “I think people should be shown the views they’re against almost as often as the ones they support, just so they’re aware of what others think.”

Since echo chambers validate people’s existing beliefs, and simultaneously keep them from hearing the beliefs of others, they make people increasingly polarized and reluctant to accept opposing viewpoints. This polarization is then exacerbated as each chamber shifts people’s perceptions of truth and dictates what views are acceptable.

“[Having no echo chambers] is a really good thing,” freshman Scott Miller said. “Being able to hear opposing opinions lets people broaden their understanding of a topic, and not have strict personal opinions about something because they only hear one side.”

An example of the polarization of truth by algorithms was detailed by Google engineer Guillaume Chaslot in the July 10, 2019 episode of the New York Times’ “Rabbit Hole” podcast. In the aftermath of a 2011 protest in Cairo, people who originally viewed pro-protestor content on YouTube were only recommended similar videos in the future and vice versa for pro-police content. The algorithm divided viewers into echo chambers that provided them with two different interpretations of the facts, and thus radically different ideas of the truth.

Free speech involves not just expressing oneself, but also listening to and engaging with others. Echo chambers make the latter difficult, as people cannot even agree on what is fact and fiction. As a result, productive conversations are becoming less common. This unproductivity has even seeped into the lives of many teens, who witness or engage in such fruitless conversations regularly.

“On social media I have seen many conversations between people with opposite views,” Smith said. “There are many conversations where they just share their side of the situation and at the end they agree to disagree and their conversation ends. But, on the other hand, I have seen many conversations between people on the opposing sides argue and threaten each other over something that could be so small. Those conversations are unproductive.”

Further, content creators within echo chambers often resort to clickbait as they compete for the attention of users. The hyperbolic or misinformed content that they are spreading ultimately contributes to radicalization and erroneous beliefs.

“Seeing misinformed information about certain political topics can suppress people about how they truly feel and can manipulate them to think [a certain way],” junior Drake Goldapper said.

Teens are especially susceptible to believing fake news, in part because they have trouble determining the credibility of the information they see online. In a 2016 study conducted by Stanford University of practically 8,000 students in the United States, it was found that less than 20% of high schoolers questioned fictitious claims seen on social media platforms.

Teens’ susceptibility to the radical ideas spread by echo chambers contributes to the psychological phenomenon of groupthink. Groupthink refers to situations in which groups of people are led to make poor decisions because they desire consensus. It occurs when there are no dissenting voices in a group, and when people would rather agree than make well-informed decisions.

There are many instances in which groupthink can occur. It may take place when a jury is deciding on a verdict, as well as when teens are introduced to the homogeneity of an echo chamber.

“I think only hearing one viewpoint can have negative consequences because then one would not be able to be fully informed about the situation to make an opinion,” senior Sydney Moed said. “The opinion could be seen as invalid since they would not have all the facts. These negative consequences can cause people to make poor decisions, as they will make decisions based off assumptions or conclusions that may be untrue, but they wouldn’t know since they only have one viewpoint.”

Echo chambers do not solely consist of political ideology either. They can also repeat and reinforce social ideas, which can have vast ramifications when the ideas are harmful. On TikTok, for example, echo chambers exist in which eating disorders and other mental illnesses are romanticized. This romanticization can then push teenagers to engage in mentally and physically destructive behavior.

Political Content Limit

While algorithmic censorship is subtle, some social media sites have taken more deliberate action to limit the types of content posted on their platforms. One of the most notable examples of this is Instagram’s automatically imposed political content limit.

The rollout of the limit began in March 2024, as confirmed by Meta–the parent company of Instagram, Threads and Facebook–and was implemented without any in-app notifications. The limit has to be manually turned off, and it inhibits the amount of political content users see from the people they do not follow.

Meta has claimed that the limit was intended to reduce polarization, and plenty of users agree with the notion that they should have the option of limiting political content on their feeds.

“I feel like limiting the amount of political content that users see is a good thing,” Polapelly said. “It reduces the overwhelm, because I know a lot of people who don’t want political content on their feed. It also prevents misinformation. When I’m scrolling on Insta, I always see misleading posts going viral. I can’t tell what’s true anymore.”

However, the company’s vague definition of political content, lack of notifications about the limit and refusal to share who determines what content is political, has led many to accuse Meta of censorship, including 57% of MSD students.

“I think this [the limit] is a bad thing, because it is limiting the political information people are receiving,” Moed said. “If a user only gets political information from the accounts they follow, they will only be exposed to one way of thinking and, therefore, not be able to come up with a well-rounded opinion about a political situation. Social media is a very important resource for political commentary for many people; even if people don’t agree with that, limiting it can only do damage.”

On Instagram, it states that “Political content often refers to governments, elections or social topics that affect many people.” The inclusion of social topics in the definition of political content indicates that any social issue could qualify.

Britannica defines a social issue as “a state of affairs that negatively affects the personal or social lives of individuals or the well-being of communities or larger groups within a society about which there is usually public disagreement as to its nature, causes or solution.” Britannica accompanied that definition with examples of social issues, which included civil rights, domestic violence, climate change, hate crime, obesity, pollution, homelessness, mental illness and child abuse.

“I think the limit is a bad idea because it’s censoring our ideas and thoughts on the internet,” junior Laina Armbrister said. “Free speech is the First Amendment in the Constitution and the limit doesn’t allow us to exercise that. I think the inclusion of social topics is also bad because it doesn’t allow people to fully see the good and the bad of social media.”

The broad range of topics that may be considered political by Meta means that anything from posts about the Palisades fire–which has to do with climate change and homelessness–to the movie “It Ends With Us”–which has to do with domestic violence–could qualify to be restricted from users’ feeds.

“I think that the social content limit on Instagram is a bad thing because it could hinder the ability for users to raise awareness about crucial social issues or share personal stories that are important to communities,” freshman Bridget Kaplan said. “It could also silence or exclude voices that rely on platforms like Instagram to speak out against injustice, So, the inclusion of social topics in the limit seems overly broad and could stop valuable conversations and activism.”

Given that teens heavily rely on social media platforms for news, if they do not know about and turn off the political content limit, it is possible that many will no longer be informed of current events. In a 2024 survey of teenagers by the New York Times, it was found that “almost all” of the survey’s 400 respondents said that they mainly get their news from social media.

When this is coupled with the fact that a minority of teens actively seek out news elsewhere, the implications of the limit are particularly palpable. Common Sense Media reported in 2019 that every day only 23% of teens get news from phone notifications or news aggregators, only 15% get news from news organizations and only 13% get news from the television.

“I do get my news from social media,” Siler said. “If I couldn’t, I’d be much less informed of what’s going on in the world because I’d prefer to get my information from apps like TikTok, [rather] than having to go out of my way to look for articles or watch the news.”

Whether or not teens keep up with current events has no effect on the fact that these events will shape their futures. For this reason, many find that staying informed is important. If social media is how teens are accomplishing this, limiting such content might be doing a disservice to the generation that makes up a bulk of social media’s users.

Conclusion

As the U.S. continues to adapt to the digital age and Americans become increasingly reliant on social media, it is probable that the government will attempt to regulate and control these platforms in the future.

The first waves of this are already being seen at both the state and federal levels of government. In 2021, Florida and Texas passed laws authorizing their legislatures to regulate the content moderation practices of large social media platforms. Then, in January of this year, the Supreme Court upheld a law that bans TikTok in the country—although the law is not currently being enforced by the Trump administration, it remains in effect.

These attempts at controlling social media platforms have prompted many to question their constitutionality. The TikTok ban in particular, has raised much suspicion about the extent to which it infringes upon Americans’ First Amendment rights.

Still, the future of content moderation on social media remains to be seen, as does the government’s role in it. What is definite is teens’ continued presence on social media platforms; it is them who will reap both the rewards and repercussions of whatever is to come.

![National Honor Society Sponsor Lauren Saccomanno watches guest speaker Albert Price speak to NHS members. National Honor Society held their monthly meeting with Price on Monday, Nov. 4. "[Volunteering] varies on the years and the month, but we have started a couple new things; one of our officers Grace started a soccer program," Saccomanno said. "We have been able to continue older programs, too, like tutoring at Riverglades. NHS's goal is to have as many service projects as possible."](https://eagleeye.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/xNOeKNVwu7aErpVyJHrHogagZUUcLLosjtbIat94-1200x900.jpg)

![Ice Ice Baby. Skating to "Waltz" and "Romance" during her long program, figure skater Ava Zubik competes at the Cranberry Open in Massachusetts on Aug. 12, 2022. She scored a total of 86.90 on her short and free skate program, earning fifth place overall. "I try to make it [competing] as fun and enjoyable as I can because it's my senior year, and so I want to really enjoy competitive figure skating while it lasts," Zubik said.](https://eagleeye.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/skater1-799x1200.jpg)