*This story was originally published in the first quarter issue of the Eagle Eye*

During a varsity ice hockey practice at the Florida Panthers IceDen in Coral Springs, seniors Matthew Hauptman and Matthew Horowitz were practicing a drill to improve their agility. As they attempted to jump over a cone on one skate, they both fell and hit their heads on the ice, resulting in concussions for each of them.

Accidents similar to that of Hauptman’s and Horowitz’s can occur in any contact sport, during a practice or competition. When these types of events happen, athletes may be barred from playing for anywhere from a game to a whole season, but, more importantly, they could experience permanent brain damage.

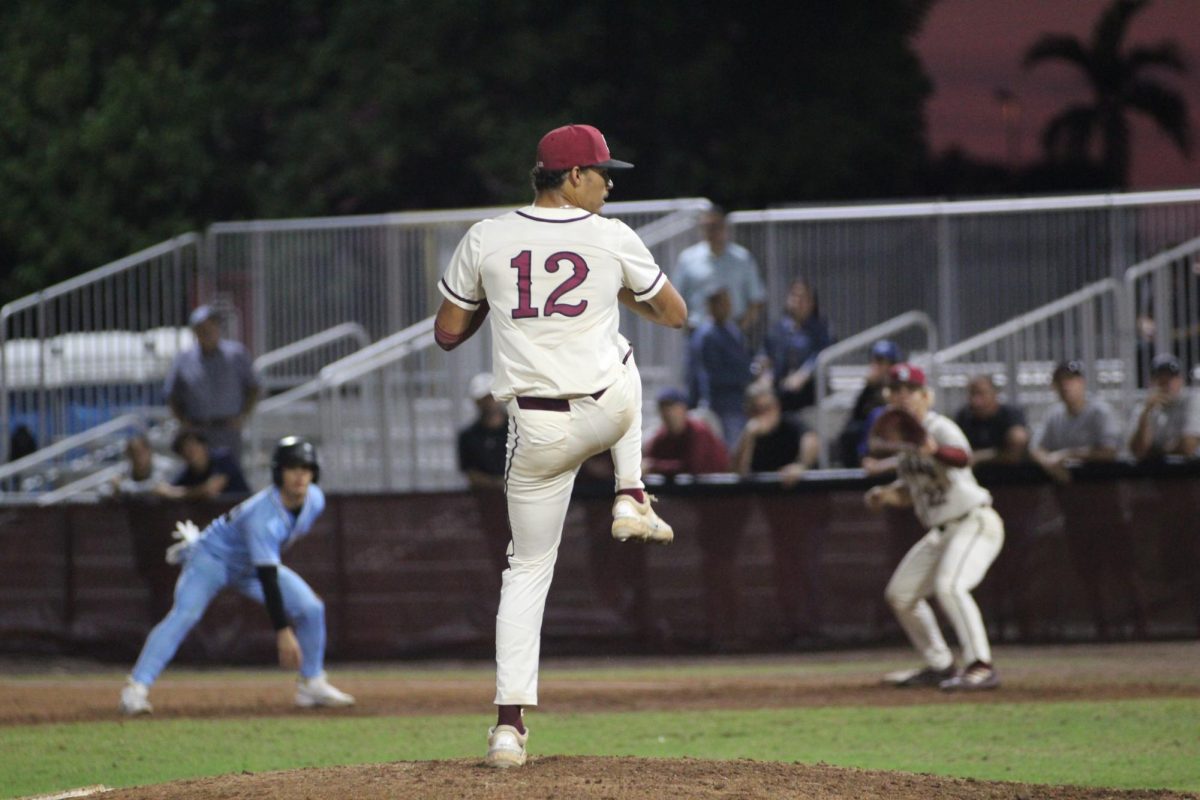

Contact sports are not only high-energy sports, but also high-risk sports. A major concern in the world of athletics is head trauma. Concussions occur frequently in contact sports, and they have the ability to leave a lasting impact on the brain.

“After my concussion, all I could do was lay down; even watching TV hurt my head,” varsity lacrosse player Thomas Frank said. “I missed like six games because of it.”

After multiple blows to the head, it is possible that the person affected may develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative brain disease found in those with a history of repeated head injuries.

Dr. Bennet Omalu discovered CTE in 2002 while examining the body of Mike Webster, a former NFL player of 16 years. According to ESPN, CTE has since been identified in the bodies of over 99 percent of NFL players studied by a Boston brain bank.

The danger in CTE is that it can only be diagnosed after death by analyzing brain tissue. Athletes often do not consider the potential physical repercussions that can result from contact sports because they will not witness it within themselves.

The illness is caused by a protein called hyperphosphorylated tau that forms clusters surrounding blood vessels within the brain. CTE slowly progresses over time, and it does not begin to show symptoms until several years following the trauma. CTE is characterized by an inability to carry out mental processes and frequent mood swings.

These mood swings consist of impulsive behaviors and outbursts. CTE may even be the source of homicidal or suicidal thoughts. After NFL player Aaron Hernandez was arrested in 2017 for first degree murder, he committed suicide in prison. When his body was examined following his death, doctors found that he suffered from severe CTE.

Hernandez was diagnosed with stage three CTE. There are four stages to the disease, which were first defined in 2012. Symptoms of each stage vary and increase in intensity over time. Common symptoms in stage 1 include severe headaches and difficulty concentrating. In the second stage, those affected begin to struggle with emotional incapability and short-term memory loss. The symptoms of stage 2 are heightened in stages 3 and 4. During stage 4, people with CTE may experience symptoms similar to those of dementia.

“There is no such thing as a safe blow to the head,” Omalu said in an ESPN interview. “And then when you have repeated blows to your head, it increases the risk of permanent brain damage.”

Although schools have become more mindful of the possible dangers that can arise due to participation in contact sports, athletes still do not completely understand the impact of the sports on their future physical and mental health.

“I believe contact sports can harm my health, but it is worth it,” Hauptman said.

For many athletes, the positives of playing their sport outweighs any possible negative outcomes. State and county organizations attempt to find ways to protect their athletes while still maintaining the integrity of the sport.

“I know playing contact sports puts my health at risk, but it is so much fun,” Horowitz said. “You can’t live your life in fear.”

The Florida High School Athletic Association and Broward County Athletic Association set regulations in place, in the event of an injury, to ensure safety among athletes.

According to the FHSAA Concussion Action Plan, “an interscholastic student-athlete who has been removed from play due to a suspected concussion may not return to play until the student athlete is evaluated by a licensed health care professional familiar in the evaluation and management of concussion and receives written clearance to return to play from the appropriate health care professional.”

The Broward County Athletic Association requires athletes to receive a physical examination from a medical doctor before they can participate in a school-sanctioned athletic activity. In order to maintain security, the BCAA establishes guidelines for safety in athletic competition and administers baseline tests to athletes on computers. The majority of MSD sports complete a concussion test every year, but hockey is only required to take a test every two years.

“For major contact sports, we have baseline testing at the school,” BCAA commissioner Shawn Cerra said. “If anyone has concussion symptoms, we take a look at the baseline data, and we discover how severe the concussion is.”

In case of emergency, the BCAA requires a medic on site during competitions. The association maintains partnerships with Nova Southeastern University, Broward Health and Joe Dimaggio Children’s Hospital at Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood, Florida to foster a safe environment for athletes.

According to Head Case, an organization dedicated to athletic safety, 33 percent of all sport-related concussions happen during practice where a medic may not be present. It is the responsibility of the coaching staff to manage injuries during practice.

Head Case also relays that one in five high school athletes will endure a concussion at some point during the season. No matter what safety measures schools and athletic associations take, it is impossible to completely prevent concussions from happening.

“I think people need to be educated about the sport they are playing in so that they can have a healthy body, but they also need to recognize the risks of playing contact sports,” Cerra said.

It is up not only to the coaches to protect their team, but also the athletes themselves. Recognizing the dangers of playing a contact sport can motivate athletes to be more conscious and aware of future impact during a game.

“It is a contact sport; you are going to have injuries,” junior varsity football player Christian Higgins said. “As long as you are safe with it, and you are not head to head, you will be fine.”

Even if an athlete like Higgins is mindful while playing, the only concrete way to prevent concussions is to abstain from playing. However, this is not a desirable option for many athletes if they plan to pursue the sport later on. In the future, ways to enforce safety in athletics—other than abstaining from participation—may come into fruition.

Technology made to improve athletic safety is already in the works. This year, a new helmet created by Vicis, called the Zero1, was introduced to about half of the NFL teams.

The material used in the helmet rebounds impact on the head. The helmet is said to diminish the impact of future head injuries on the brain and even decrease the percentage of NFL athletes diagnosed with CTE.

When utilizing devices like the Vicis Zero1, the amount of head injuries witnessed in contact sports may decrease significantly. It is possible that future athletes may not even associate with the common lingering fear of lasting head trauma and CTE.